Dark-eyed Junco singing its head off at sunrise

What Birding Does For Us

Birding is seen by many as a diversion from normal life, and I assume most birders would attest to this on some level. There's something about basking in a forest alive with song or sifting through a mudflat of calidrids that allows the rest of life to simply fall away for a moment. If my mind is occupied by the stunning color of a Lazuli Bunting or consumed with sorting out the identity of a migrant empidonax, then it is not distracted by an ever-filling email inbox or the finer points of a grocery list that complies with my oddly-timed Whole30 decision. If my body is on an observation platform overlooking a marsh, then it is not in my chair at work. Conditions in the field can be woefully uncomfortable yet infinitely more peaceful than the stressful situation awaiting back at work or home. Birders know diversion well. That part will always be there.

But there is much more to this silly hobby. A restorative effect is in play much of the time. The endless song of a Pacific Wren has a way of putting me back together every time I hear it, often in a way I didn't even know I needed. The thrill of finding a rarity or simple pleasure in the beauty of a common species can carry all the satisfaction of nestling the final piece of a puzzle into place. It's the deep breath that brings the heart and mind back to center. And with this needed exhale comes the power to get back to the demands of life. Some take to the woods and mean never to return, but I think most of us do so precisely because we know we must return, and we want to come back as whole persons.

Yet beyond diversion and restoration I find birding functioning on another plane. I often think of it as a sort of metonymy for real life, everyday life. With its joys and disappointments and seasons and gambles and overwhelming call for sustained attention, surely birding is simply practice for the rest of our lives. Birding—and any attentive engagement with the natural world, for that matter—isn't an escape from real life, but a return to it, participation in it.

I've been thinking more about these things lately because current circumstances are keeping me closer to home, and birding has been an important focal practice for me in this season. Thankfully, my closer-to-home birding habits were already in the works before this time of restricted travel was forced upon us. They've taken on a new life in the midst of the pandemic.

One of the bazillion Orange-crowned Warblers seen in April

Birding Locally in a Time of Coronavirus

Last year Jen Sanford's Five Mile Radius movement bounded onto the birding scene and caught the attention of many. The rules are simple: draw a five mile radius around your home, then go find all the birds in that circle. Instead of devoting time to chasing rarities and building state lists, save a few tanks of gas and see what shows up right in your own backyard. I was a fourteen-month-old dad when I learned about the idea, so I jumped at the opportunity to give my birding efforts a more local flavor. The Five Mile Radius (5MR the rest of this post) shaped the way a large group of birders approached their birding in 2019.

No one had a clue how much we'd need it in 2020.

In January we were hearing the word coronavirus for the first time here in the states. In February it mostly felt like someone else's problem. In early March we were told it would magically disappear like a miracle, but instead it made its way to U.S. soil. We did our collective best to downplay the whole issue, but on March 11 the NBA took decisive action by suspending its regular season, and our sports-worshipping country finally decided to take the matter seriously. Within a couple weeks governors across the country, including Oregon's Kate Brown, issued some version of a Stay at Home order, and everything came to a sudden halt. The shock to the system was real, but it paled in comparison to the suffering that was already piling up around the globe.

For the safety of others, we're all mostly staying home most of the time. Other than getting out for groceries or other essential services, the one thing we're allowed to do still is get out for a walk or some exercise. And any trip out and about must comply with social distancing parameters. As an introvert and a birder, I feel more than adequately equipped to take these restrictions in stride.

Enter April, 2020, our first full calendar month on lockdown. With so much up in the air I didn't dare concoct plans of any sort, especially those of the birding variety. Instead, I stayed more local than I ever have for a full month. I did not set foot outside my 5MR at all in April, and the result was one of the most rewarding months of birding I've ever experienced.

Golden-crowned Sparrows are looking soooo fine in April

The Birds

The fun kickstarted the first weekend of the month with a long overdue 5MR lifer Northern Harrier hunting over my favorite local spot, Stewart Pond. But the best find of that weekend, and probably the whole month, came while I was on a run. One of the main drawbacks to running (other than the part where you're putting one foot in front of the other for miles at a time) is that it makes birding quite difficult. Still, I like to pay attention to what I see and hear, and I often keep a list of birds I can identify while pitter-pattering along.

On Sunday, April 5, I was running my normal route along Pre's Trail through Alton Baker Park when I came upon a cedar full of passerines that were losing their minds. Chickadees and kinglets and warblers and bushtits were all adding to the cacophony, and I knew something was up. I stopped the tracker on my watch and slowly tiptoed under the tree, hoping I could find the source of the agitation. Sure enough, an owl was sitting quietly and trying to ignore the noise, but it was not the one I was expecting—a Northern Saw-whet Owl was staring back at me!

I was elated. Any owl seen during the day is grounds for celebration, but a Saw-whet is a rare treat. Plus, this was a county lifer for me, and of course, and lifer for the 5MR.

But I had a problem. With no phone on me, I didn't have a way of snapping even a poor photo of the bird, or any means of getting the word out about the owl. So I ran home faster than usual, picked up my phone and my gear, and called John Sullivan on my drive to the parking lot closest to the bird. Thankfully the bird was still there when I got back. I spent a while enjoying it from a safe distance, which is far more than six feet when it comes to owls. Over the course of the day dozens of birders got to see it, and I'm grateful so many got to share in the joy of this little floof.

Northern Saw-whet Owl

Alton Baker Park

Sunrise at Spencer's Butte

Once I arrived at the summit I took a seat and planned to watch the scene unfold. Almost immediately the "qwerk!" of a Mountain Quail burst out just below me! I had Mountain Quail up here twice last year, but I only heard them. This one stepped out into the open for a few moments, which was just the third time I've ever seen one of these secretive little birds. I had to make do with my scenery lens, so the photo is awful, but I still managed to capture the bird in its quintessential habitat.

Mountain Quail

If you can't see it that's fine

As the quail scurried off into the bushes, a bird flitted up into the tree right in front of me. It was backlit so all I could make out was a silhouette, but I knew what it was right away: my 5MR lifer Townsend's Solitaire! And as I watched, another one joined it!

Townsend's Solitaire

Spencer's Butte

The good times continued that morning with another 5MR lifer, this time a new shorebird: Dunlin! I had a brief flyover at the Tsanchiifin Walk, then a whole flock at Danebo Pond. Amazingly, I would end up encountering them seven times over the course of the month after having never seen one in my radius.

One key to birding the 5MR well is repetition, habit. Find the areas that are likely to produce good birds, then check them relentlessly. This is the best way to find rarities, of course, but it's also the perfect way to get in touch with subtle shifts that happen from day to day. Migration in western Oregon has a dramatically different feel than it does in the midwest. Instead of concentrated waves hitting in short periods, it's a slow burn basically all the way from mid-February to early June. Getting baptized in a shower of warblers on the Chicago lakefront will always be something I miss about my days in the midwest, but the incremental changes we get to observe here have won me over.

For instance, for a couple of weeks in April Stewart Pond was positively stuffed with Lincoln's Sparrows. They winter here, and a decent number actually breed in the county up on the western slope of the Cascades, but I never tire of seeing them. Just look at the intricate detail on this bird.

Lincoln's Sparrow, with a supercilium matching the background for style points

Stewart Pond

Speaking of birds matching their background, check out this nearby Western Bluebird!

Someone once asked me why they're called bluebirds if they have orange on the chest

I don't know how to help these kinds of people

The Stewart Pond + Bertlesen Nature Park complex is the one that I check most frequently. For much of the Winter and Spring, a female Cinnamon Teal moved between the ponds in this area—though it usually preferred not to be photographed.

Cinnamon Teal accidentally hanging out in the open

Bertelsen Nature Park

If you don't like the flowers + birds combos of Spring, I don't know how to help you either

Bertelsen Nature Park

The following weekend started with a bang as I bagged another Lane County lifer in the 5MR. There's a little collection of ponds at the western extremity of my radius, and I like to swing by when I'm in the area because one day there will be an ibis there, I'm sure of it. Usually there's a Great-blue Heron, and Greater Yellowlegs frequent the spot. Both of those birds were present when I pulled up on April 18, but as I rolled my window down something else caught my attention. From the field on the other side of the ponds came a few piercing high notes followed by a unique, garbled song—VESPER SPARROW! I scrambled around the ponds and spent the next half hour chasing down three of them as they flew from bush to bush. This was a full blown county nemesis for me. I assumed I'd finally track one down in a hedge row one of these Falls, but finding three together, with one singing away—and in my radius no less—was so much more rewarding.

Vesper Sparrow practicing for his on-territory days

Balboa Park

It was a close call for the 5MR list:

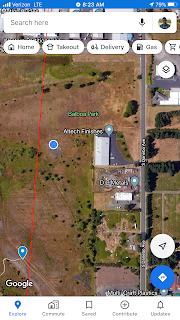

The blue dot is me, looking at Vesper Sparrows

Everything to the left of the red line is non-5MR land

On the way home it was back to Stewart Pond for my first Solitary Sandpiper of the year. This is one of the most reliable places in the county for this tricky Spring migrant. Can you think of a better name for a social distancing species than SOLITARY Sandpiper? This is false advertising though. There were two at the pond.

Solitary Sandpiper, but close to another one, thus betraying its name

Stewart Pond

While repetition is an essential component of the equation, exploration is another. Nearly five years into living in Eugene, I feel like I'm barely scratching the surface of the potential birding areas near me. I currently have 58 locations that I have birded at least once within five miles of home, and I added five of those in April alone. One place that I visited only once last year was Melvin Miller City Park. I returned on April 19 and was treated to a close encounter with a pair of Pileated Woodpeckers, which are far easier to hear than they are to see.

Pileated Woodpeckers are the size of a crow, and very loud

Melvin Miller City Park

That same day Vjera Thompson made an incredible find for Eugene: a Red-naped Sapsucker! Thankfully it stuck around long enough for me to add this third county lifer in the 5MR in April!

Red-naped Sapsucker, kind enough to lack signs of hybridization

Mulkey Cemetery

On April 20th my 5MR year list stood at 135. I made it my goal to hit 150 by the end of the month. Here's a few of the highlights from the last ten days:

Not new, but a nice male Cinnamon Teal and another Solitary Sandpiper

that won't live up to its name (also a Green-winged Teal in between)

Bertelsen Nature Park

Western Kingbirds have been coming through in droves this year!

Skinner Butte

Dusky Flycatcher showing that cute round head and short wing projection

Click here to hear its distinctive "whit" call

Rasor Park

Hammond's Flycatcher showing the characteristic crested look and longer wings

Click here to hear its distinctive "pip" call

Skinner Butte

Finally got a (very poor!) photo of a Calliope Hummingbird in Oregon

Bloomberg Park

Western Sandpiper is a regular Fall migrant in my radius, but I had some fancy looking Spring migrants a handful of times in the last couple weeks (shorebird #9 this year for the 5MR)

Stewart Pond

One of an astonishing FIVE Olive-sided Flycatchers in one place—personal high count!

Skinner Butte

At 148 with a couple days left, I joined a group of birders before work this past Wednesday and took to the hills behind LCC, and the birds were abundant. The year birds for me included a Great-horned Owl along one of the trails, a Western Wood-Pewee, and these two:

Yellow-breasted Chat, coolness overload

Hills Behind LCC

Chipping Sparrow is less cool, but I was grateful to finally find one of these cuties

Hills Behind LCC

And that was the final puzzle piece for April. Last year I had 158 species all year in my 5MR, and by the end of April I'm already at 152, with 137 of those being found in April alone. Three county lifers, and three additional 5MR lifers. What a month.

Was the birding THAT much better than usual this April? Perhaps. But I doubt it. I just think I was paying closer attention closer to home.

And the more we pay attention, the more things come to the surface. Birding is just practice for real life.